Conversations

-

Hanging out with Asha

From a studio visit with Asha by Eliezer Sobel

…she likes to look at the Big Picture. She is one of those rare beings who seems to be joyfully connected to her life and work and the Great Mystery in a very real, down-to-earth way that is a magnet for the wandering souls, minstrels and poets who often appear in her orbit.

We had the following conversation about spirituality and art in her studio …

-

Lama at 50

By Rick Romancito of The Taos News

Lama, it turns out, truly exists in the hearts and minds of the people who have landed there in a search for something humans have sought from the beginning of time. At times, it has been fulfilling and a path toward enlightenment. For others, it has been a disappointment, but all along, it has been a work in progress that continues to grow and evolve.

An interview with Asha — Reunion, ceremony and remembering part of solstice-week celebration at the Lama Foundation

-

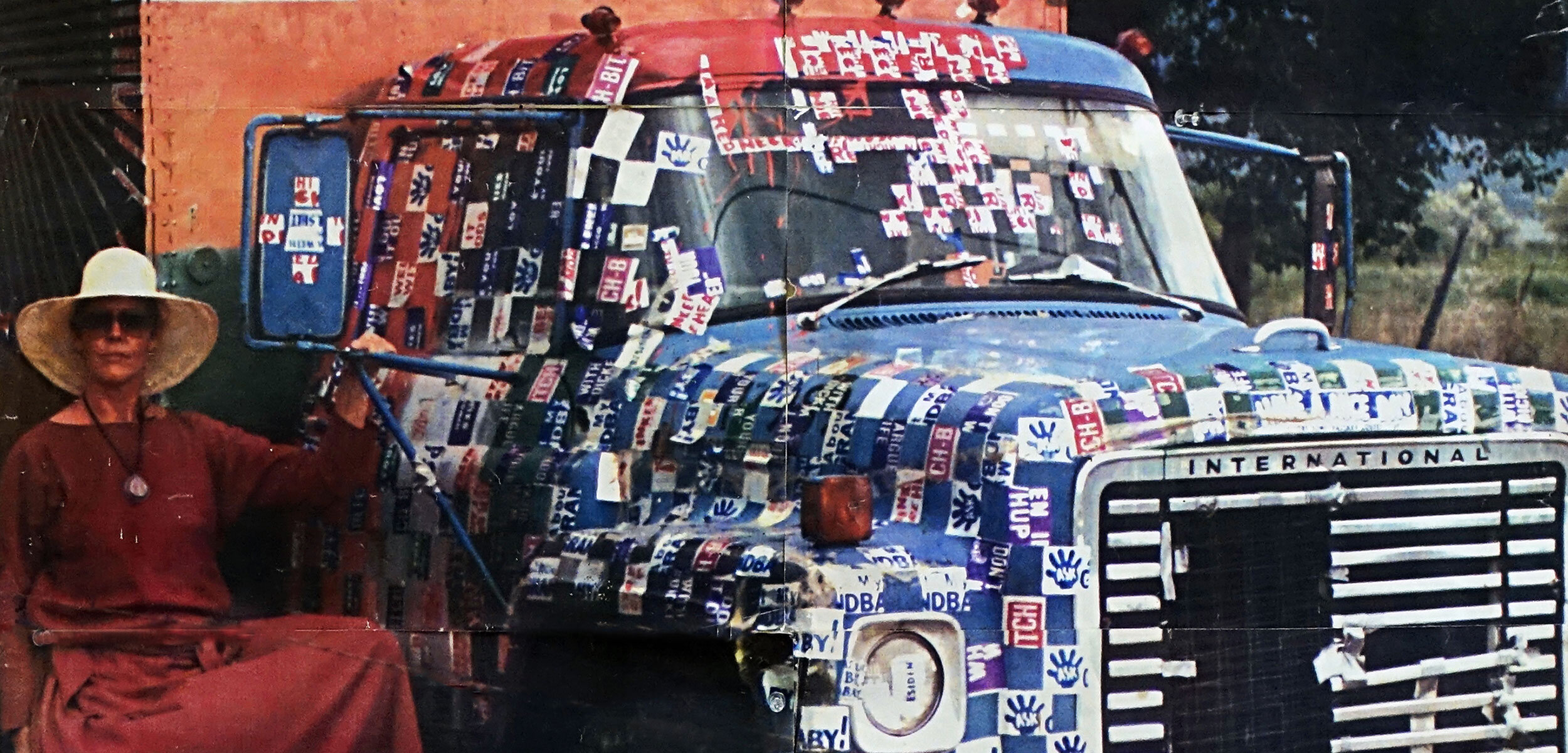

A Picture of Asha

From the foreword to “40 Days Alone, A Visual Chronicle”, by Eliezer Sobel

…. but she seemed to fearlessly follow her nose wherever it led… to hang out with her is a ride like no other, sprinkled with her unique observations on all topics mystical and mundane, bound to include at least a dozen meaningful encounters a day with complete strangers, often involving one or two new schemes to save either the world or an individual, and most certainly liable to contain several outbursts of pure, unadulterated mirth and laughter.

Hanging out with Asha Greer in her Studio

Wild Heart Journal. By Eliezer Sobel

Asha Greer is perhaps most notable for her role in creating, and helping to sustain, the Lama Foundation in New Mexico, the 31-year-old spiritual community which originally published Ram Dass’s famed Be Here Now, for which she actually did many of the illustrations. She is the mother of four daughters, and currently resides in Batesville, Virginia, where she works several shifts a week as a nurse. She was the founder of the Hospice program in Charlottesville and is apparently a wonderful person to have around if you happen to be dying. Asha also teaches Japanese Tea Ceremony, maintains a beautiful garden, and serves as a home base and support system for many pilgrims on their way—her house is literally open at all times: there is no lock, and no key. She is a Murshida in the Sufi world. and travels the country teaching in that capacity. And finally, or perhaps primarily, she is a painter. She had her first public show a year or so ago in Charlottesville.

I first met Asha in Jerusalem in 1988. She was at the tail end of a solo trip around the world, triggered by her mother’s death and a subsequent 40-day retreat. We walked the streets of the Old City and the desert wadis together, and I came to recognize in her both a kindred spirit, an inspirational, positive force, and what I sensed would be a life-long connection. A year later I showed up at her door to do my own 40-day retreat in the cabin atop the mountain across from her house, (where Wild Heart Dancing was largely created) and in February of ’91 I turned up again, and essentially never left. I lived in her home for four years, and now have my own place about ten minutes away.

It was an exciting creative time: we’d each seclude ourselves in our studios for long hours, and then meet for tea and conversation, sitting on the funky old couch on her porch which looks out on the pristine silence of the mountains. In the spaciousness of that vista, she would invariably raise the level of any conversation out of the merely individual point of view to an all-inclusive perspective; like her wall-sized canvases, she likes to look at the Big Picture. She is one of those rare beings who seems to be joyfully connected to her life and work and the Great Mystery in a very real, down-to-earth way that is a magnet for the wandering souls, minstrels and poets who often appear in her orbit. We had the following conversation about spirituality and art in her studio early last summer. Asha has a tendency to free-associate. As an editor, I’ve decided to share her mind-streams with you as they occur, rather than trying to cut and paste her into a more linear dis-course. Don’t think of this as an interview, think of this as hanging out with Asha in her studio.

ASHA: First of all, I have to talk about what I think spirituality is—which is not something that focuses on anything that isn’t right here. I.e., spirituality is not about getting to heaven, going to hell—heaven and hell are right here—there is always and only this moment. So we stride along kind of creating a reality, but mostly it’s a mystery, okay? And it seems to me that what we’re all looking for is what is called “calm and peace,” and often we don’t know what it looks like, but we know when we’re in it. So I know I’m in it most of the time now, and I’m very happy because I’m 62 years old and I never thought that it would be like this—so great, and totally not dependent on external circumstances, but probably a little bit dependent on my passion for something. I don’t think it matters what you have a passion for, but there has to be engagement. Engagement causes concentration and concentration causes happiness, and if you don’t get your dose of happiness everyday something always feels a little wrong, so I think maybe as I’m getting older my doses of happiness come not so much from formal sitting practice—I really need something to do, so making paintings is a good thing for me to do.

So that’s where spirituality and art come in for me. I’ve done tons and tons of what are called spiritual practices and when I get depressed, I use them. Mostly the ones that work are based on the breath, so for one, I try to make paintings about, you know, air going in the nose, air going down the spine, air coming up the spine—graphic descriptions of what worked and happened for me. And then I’d done that enough and I got bored with it, and then I did my 40-day retreat, and I did a drawing every day—and the drawings that I liked and which were the most fun were either funny or beautiful. In terms of beautiful, I was concentrated and engaged and looking at what I was looking at and doing the eye-hand coordination to get it down on paper, and I had that interior excitement that demands total calm—it’s kind of like getting down into your deep deep deep belly so that you can make a good note on the Shakuhachi—it was like that. But it doesn’t seem to me that the subject matter particularly matters—and that what one does in art is no different than what one does in the garden, or cooking, or driving to work—I work in a hospital as a nurse, so it’s how I work with the patients.

WILD HEART JOURNAL: If subject matter truly didn’t matter, you could be doing a picture of the dark forces, equally demanding of concentration, and therefore, a spiritual exercise.

ASHA: Well...one of the things I have learned over my life is that if you invite dark forces in, they come in, and I’ve never had much of an attraction for dark forces—I don’t like them. So basically, the whole astral plane is one that I think you move through into a much more subtle light plane, so I don’t get into the dark forces. And every so often I’ll make the mistake of going to a movie that has an indifferent idea towards how people act with one another, where there’s a kind of indifference about everything— “Who cares? Who cares if we kill somebody? Who cares if we rape somebody? Who cares if we treat somebody bad—it doesn’t matter.” Although I realize all that comes out of pain, the media doesn’t treat it as that—the media treats it as something glamorous and it always brings me down. I always have these awful images in my head after-ward. So I don’t like dark images. I don’t like all that stuff, so I don’t invite it in. Like this painting here is white: I’m looking at light, I’m trying to see what’s it like to have it all white. Is it too boring? For six months now it has been fascinating to me, because it’s white but it’s also completely full, but it’s not luminous yet. I have to keep working on it until I can make it truly luminous without using direct light. Like you could do windows with light coming through the windows—that’s luminous and everybody recognizes it’s luminous, but I’m trying to get more abstract luminosity with pure white.

WHJ: Getting back to something you said before—about what occurs when you’re gardening with concentration, cooking with concentration, or painting with concentration...

ASHA: Engagement. For me, I can’t concentrate unless I’m really engaged. And my attention span is about an hour, so basically, you know, if I’m driven...obsessive is the best, because then you’re just totally driven and having a great time doing something. It’s like eating a fabulous meal when you’re also hungry—it’s just, “mmmmmm.” So I like it when all the motors are going, but I like it when they’re stopped too, because there’s this interior place where the motors are also going and it has a kind of an internal song. And I guess that’s what this painting is trying to deal with—what is the texture of the internal song, where it’s calm and peaceful, but not boring? Because that’s the edge, the edge that everybody who sits has to deal with, it’s the edge people are dealing with all the time. I’m sitting, I’m watching my breath go in and out, “boring, boring, boring, boring”—but it’s not boring, it’s never boring, there’s always the heartbeat, or the thrill of the massage of the breath as it comes in and it opens up the ribcage, or the hurting leg—you know when you’re sitting the hurting leg is like seven trains going by in Grand Central Station—I mean it isn’t boring. But we have these ideas about it, so basically, I’m just trying to explore the place that I feel is really peaceful and calm but not necessarily still, and not stopped—it’s all verb, everything. So, how to catch that in things that don’t grab you and make stories? Like if you look at this painting here, which is all white, and it’s horizontal, it implies land and sea and mountains and sky, but only if you want to see those. It doesn’t really imply anything. Basically, you can read into it anything you want—or you can read what it is, which is white paint on a canvas that is just enough stimulus for the eye to rest on. And there’s depth, because there are lots of layers on it.

WHJ: How does this kind of technique which doesn’t involve careful brushwork or realistic representation, but is more just applying paint with a big, glopppy old brush and then blotting it with paper—how does that get you concentrated? Does it?

ASHA: Yeah it does—it engages the whole body. I guess it’s kind of gross, the engagement of it. Basically, I can look at it for maybe ten or fifteen minutes at a time, then I put it on a wall some-where in the house and forget about it, then I look at it, then I come to another coat. To get concentrated on a more refined level I do small oil paintings, copying little things—there’s a whole range.

WHJ: There’ a quality of mindfulness that one might aspire to in sitting practice, where you’re mindful of the breath, mindful of every mind moment, being aware—and then there’s this quality you’re talking about, when all the motors are going and there’s obsessive engagement and concentration. Is there a relationship between that and mindfulness? Because in the Buddhist world some might say one is to remain mindful at all times, and not, so to speak, “lose yourself” in your work. And then I’ve heard certain artists say, “No, I don’t want to be being mindful, I want to be lost in it.”

ASHA: Well, we’re working with words: there’s “conscious,” there’s “mindful,” there’s “lost in it,” there’s all of them, and in any inbreath and outbreath there are probably a hundred of those variations going on, because mindfulness is a relative term. Do you know what you’re doing? Do you have a clear intention? Actually mindfulness, as far as I understand it, is being with what’s happening, so if you’re obsessive, you’re with “being obsessive” .... I keep going back to the great image I got from a Tibetan Geshe. He gave us this really crummy drawing of an elephant winding up a page. It starts out with this guy walking behind the elephant, pretty soon he’s holding the tail of the elephant, then he’s on the elephant, and then he’s on the head of the elephant, and then he’s on the trunk, and then he’s sitting, and the elephant is tamed beside him, and that elephant is the mind, or the untamed mind, and mindfulness is the guy sitting. So when I’m talking about obsession, I’m not talking about obsessive unconscious, I’m talking about being totally engaged and having a great time. I think the goal of all meditation and all practices is to be totally engaged as a vassal of whatever you want to call what it is that made us.

WHJ: Vassal or vessel?

ASHA: Vassal—you know, you work for the boss! But vessel also. There’re all kinds of words, but when the current is going through you, you know.

WHJ: You were saying the purpose on some level is to be engaged and having a great time. I don’t think that anybody would say that that’s the purpose of meditation.

ASHA: I think it is. I see fun and a great time as being engagement and concentration.

WHJ: Even if it’s focused on some negative aspect of oneself?

ASHA: What is negative?

WHJ: Many people sitting are being mindful of pain, suffering, tragic memories etc. They wouldn’t call it fun. But you’re suggesting perhaps it is if you’re fully engaged with it?

ASHA: I guess I’m using the term fun rather loosely. I don’t mean “la la.” I was taught a practice by Bhante Gunaratana: first you think, then you sustain the thought, then you concentrate, and then you add joy. What totally surprised me was how easy it was to turn on joy and rapture, but they are the pre-state to bliss, and bliss is pretty empty. Bliss is more like a ventilation, a space between the molecules. So I’m always trying to think of ways to paint that reflects this. What communicates this? My angel paintings were extremely popular because angels sort of imply for everybody the luminous world. But I don’t experience the luminous world as angels. I experience, to tell you the truth, the luminous world as your face, the staircase, the filthy rug, the light coming through the windows, and that enormous growth going on wild and uncontrolled out-side as the trees fill up with water and the air empties of it and then refills, the whole cycle—it’s all luminous. Either you’re here and it’s all luminous, or you’re dissatisfied and waiting for it to get luminous again. Or, if you haven’t dropped as many hormones as I have, then you’re lusting. That’s a big part of everybody between 12 and 55 I think, and men I guess longer, and some women have never stopped. But I stopped, and basically what I’ve replaced sex with is painting, which is easier—it’s not so complicated! Painting is just a practice, something to do, you have to do something between breakfast and dinner.

WHJ: Okay, but I think most people engage in a spiritual practice because they begin from a sense of confinement or suffering, or an awareness of mental prison, or separation from God, or whatever metaphor you want to use, and they engage in the practice in order to address that contraction.

ASHA: Yeah but I never was separated from God. What was hard for me was finding out that people were separated from God—it seemed so dumb.

WHJ: Well can you hypothetically address this question: if most people engage in a spiritual practice in order to get somewhere, even it’s to find out that there’s nowhere to get....

ASHA: Yeah well that’s good. When people get to where there is nowhere to get, then they’re welcome in my studio. And, the people who know that there’s no place to get also like these paintings. They’re the only people who like them. I can tell who my spiritual buddies are by the people who like these really “boring” paintings, or what one friend called my “muzak paintings”—they go with everything. But I just love them. I love this white painting. I love it better now than I did an hour ago. Whatever I did to it while we’ve been speaking, putting that texture on, al-though it’s very subtle, it has increased its luminosity. And so, anything that amps up the spirit...When I did a three-day retreat in a totally dark room, I got to nothing, to blank, to a place of “not good, not bad, not right, not wrong, not here, not there, not real, not not-real, not this, not that, not God, not not-God, not void, not not...”—you know, nothing! It was so blank, and I understood that practice is about allowing—Allahing, allow Allah.

WHJ: Have you considered just buying canvases and not doing anything to them?

ASHA: Somebody just had a show at the Museum of Modern Art that was all just straight white paintings.

WHJ: Why bother putting the white on it? Why not just put up canvases with nothing on them, to do the real Zen art exhibit?

ASHA: Well, because it’s not to be a Zen art exhibit, I’m actually trying to express something.

WHJ: You are trying to express the Zen moment.

ASHA: It’s not even the Zen moment—it’s more of a handle on it. It’s a statement about it, saying it’s the Zen moment—it’s much more of a direct thing than that. It’s just what I want to see. I want to be able to see it, to look at it. Sometimes when I’m in a bad mood, which does occur from time to time, and I come in here and I think, “Oh my God, what a waste of time, why don’t I just sit and enjoy what’s already given? You know, the lilies of the field. Why don’t I be a lily of the field? And I realize it’s because I have an enormous amount of energy and I have to do something with it, and this is a fun kind of thing to do: you know, you paint an ocean and then you’re at the sea. Plus, people like them. They go on people’s walls and there’s something that happens. I think this one is quite beautiful actually—it might be finished. Then, how to frame it, where to put it—it’s so white that if you put it on a white wall, the wall looks dirty, or it looks just like another texture on the white wall, so it probably has to go on something like a beige wall. Maybe I’ll have to paint a wall.

Lama at 50

The Taos News: Tempo

Reunion, ceremony and remembering part of solstice-week celebration

By Rick Romancito | June 22, 2017

The thing you find out right away is that Lama is not a collection of buildings, pathways, encampments and hidden shrines in the forest. It’s not even the people who call themselves “Lama Beans.” It’s something ephemeral. It’s intangible.

Lama, it turns out, truly exists in the hearts and minds of the people who have landed there in a search for something humans have sought from the beginning of time. At times, it has been fulfilling and a path toward enlightenment. For others, it has been a disappointment, but all along, it has been a work in progress that continues to grow and evolve.

For some, that’s kind of hard to wrap your brain around. Writer-translator-teacher Mirabai Starr literally came here as a child. Dropped off when she was 14, Starr was absorbed into the Lama community with open arms. And, for many years, she was the youngest member of the group, the kid everyone took under their wing, taught and protected. Now, she says, she is dealing with the idea that folks up there consider her an elder.

This week, Lama celebrates its 50th anniversary. “We are inviting everyone who has ever been touched by Lama to visit,” an announcement reads. “The world needs to hear from us. By gathering as a common tribe, we can tap into the collective inspiration of the past 50 years, and help breathe inspiration into our communities for the next 50 years.”

From now through Sunday (June 25), “simple yet abundant, we will follow the structures that have endured at Lama for years, starting with morning meditation, practice and tuning, zikr, Shabbat and culminating in a grand gathering Saturday (June 24). We will weave practices throughout, led by historic Lama teachers and returning Lama Beans, as well as an organic response to the energy and talents of everyone present.”

The celebration isn’t limited to just this week. Lama is commemorating this milestone reunion all summer through Sept. 24.

Asha Greer, formerly Barbara Durkee, is one of the founders of Lama.

We spoke with her on a June 7 visit to Lama with Mirabai Starr.

Tempo: How did you come to be at Lama?

Asha Greer: My husband and I in 1967 had a vision of starting an ecumenical spiritual community. But, it was very elaborate at that time, you know, it had the tarot deck at the bottom, the major arcana, the tarot deck and then it had ladders going up – we were in our early 20s – something like that roof there [she then pointed to the Lama dome] or something elaborate and a meditation place. We also had an idea of making wings off it for different lifestyles because it was the early ‘60s and people had so many lifestyles. We were married and we were kind of conservative, among the conservative people that we knew, and so we packed our two children into a bus and we came out here to look for land. We rented a house on the Nambé Pueblo, started meeting people in Santa Fe. The collection of people who came were many because everyone was feeling like they wanted community, but what happened was that our adviser who was in India went into retreat.

At this point, we should explain a little about Greer and her background. She is considered “a lifelong student of the human condition,” according to her website (ruhaniat.org). “She is often intoxicated with awe, fascination, or bafflement about the nature of reality. Her ‘her-story’ includes a lifelong interest in comparative religion and its influence on the brain, thought, and behavior. … She raised four daughters, and has spent years as a school teacher, a school principal, and a hospital nurse. She is a practicing artist and has created a deck of meditation cards from paintings she has done, as well as a book illustrating each day of a 40-day retreat.

Now, back to our conversation …

Greer: So, we needed another ‘adult’ – I was 25 and he was 21 – for something this big. The third member of the founders had pledged $20,000, which was a lot of money then, but not for what our vision was. So, he said he’d help us, but only if we went more modestly, if we had a spiritual motive – not a utopian motive – and if there would be no drugs or alcohol. That reduced our number from 200 to three. So, we became known as the bourgeois of the hippie movement. That’s how we came here.

Tempo: What are some of the most significant changes you’ve seen come to Lama over the years?

Greer: Well, we came to get away from the conservative world that was pretty tight and boxed-in, non-diverse and not very spiritual. When I grew up, in spite of the fact that everybody I knew went to church on Sundays, nobody talked about God. Nobody talked about love. It seemed crazy. So, we wanted to get out of that, and many other people did, obviously. So, it was very small at first. There was this building that we built and others. I don’t know what we would’ve done without the Gomez family [of Taos Pueblo], Little Joe just because he was so inspiring and then Henry and the rest of them – all that huge family – and the connection with the Pueblo was really important to us at the time. … The people from the Pueblo helped us a lot in making the adobes and in living lives that were so much closer to the land than ours. It’s changed a lot since we started because we started with the orders that we were to sit and meditate for half an hour a day and also then have discussions about spiritual things. Then, we left. We left because our marriage broke up, actually. So, I went to the east to start another community with another group of people and my husband actually went to build a place at Dar al Islam up in Abiquiú. It’s a very beautiful place, a kind of mildly used Islamic center, I think. Anyway, one of the things that has remained the same is that it’s ecumenical. Everyone was welcome here. The community has grown. … You know who Richard Alpert is? Ram Dass?

Another bit of backstory: Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary were prominent Harvard college professors who became known in the 1960s for their experiments with LSD. Alpert “continued his psychedelic research until [a] fateful Eastern trip in 1967, when he traveled to India. In India, he met his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, affectionately known as Maharajji, who gave Ram Dass his name, which means ‘servant of God,’” according to his biography (ramdass.org). “Everything changed then – his intense dharmic life started, and he became a pivotal influence on a culture that has reverberated with the words ‘Be Here Now’ ever since. Ram Dass’ spirit has been a guiding light for three generations, carrying along millions on the journey, helping to free them from their bonds as he works through his own.”

Greer: Richard had been part of our original group, and we had been living with him before when we were at Nambé Pueblo. And, he went to India and he found a teacher and came back and he wrote a book, which we helped put together, called “Be Here Now,” which was very successful and made us an income that was a little bit more secure than everybody whose parents would give them some money. There was no income stream. Then, he went back to India and he got this big statue of Hanuman that he sent over here. Our spiritual center up to that time had been in the prayer room. It was very charged in the way a sanctuary in a church is charged, charged with love and spirit, love. But, he brought the Hanuman here and I was always an iconoclast – I never liked statues – and my husband felt the same way, so we didn’t want the statue. So, it went down to Taos.

Lama today and in retrospect

Lama’s origins were simple and yet revolutionary, coming at a time when experiments in living were popping up all over the nation and the world. Here in Taos, many of the people who were drawn to Lama were often labeled “hippies” and shunned because of negative stereotypes involving illegal drugs, “free love” and pagan worship. In May 1996, the Hondo Fire served as a demarcation point in the history of Lama. Those who visited Lama soon afterward were struck by how the flames had destroyed the lush forest surrounding the site, but had left its buildings intact. It has been said the road around the main area served as a firebreak, but others still believe there was another hand at work, sparing the place for a reason.

That reason continues to inspire retreatants and longtime associates and residents. And, while it may have originated with strictly spiritual intentions half a century ago, its future is pointing to an evolution that embraces permaculture and land stewardship, thereby attracting as many youthful participants as it did in its infancy.

A picture of Asha Greer

From 40 Days Alone: A Visual Chronicle

By Eliezer Sobel

In September of 1988, I was sitting in friends’ apartment in the Old City of Jerusalem when there was a knock on the door. My host opened it, and a wild wind of a woman in a bright orange parka whirled into the room, and into my life forever. This was one of Asha’s last stops on a solo trip around the world. She was 53, roughly the age I am now, and I sometimes marvel that while I still seem to be waiting to one day grow up and figure out who I really am, she was somehow already Asha, and probably always had been: a force of nature, a fearless lover of God, and most of all, simply and honestly herself, for better or worse. That quality of striving to become somebody or something, so prevalent particularly among spiritual seekers, was conspicuously absent in her. She was already “there;” (although she would be quick to correct me: she was, I should say, “already here.”)

We spent the next three weeks together exploring Jerusalem and its surroundings, walking miles in the hot sun through the wadis (dry riverbeds that run through the desert gorges) escorted by an armed guard, wandering the maze-like narrow back alleys of the Arab suk (market), finding hidden, dark cafes down broken old stone steps beneath the street, places where I would have been unlikely to venture on my own, but she seemed to fearlessly follow her nose wherever it led, and I was along for the ride. And as anyone who knows Asha will attest, to hang out with her is a ride like no other, sprinkled with her unique observations on all topics mystical and mundane, bound to include at least a dozen meaningful encounters a day with complete strangers, often involving one or two new schemes to save either the world or an individual, and most certainly liable to contain several outbursts of pure, unadulterated mirth and laughter.

While traveling in the Arab world, she kept her hair and body covered, in the guise of a devout Muslim; in actuality, she was and is, a Sufi mystic, a Buddhist meditator, and really a transdenominational devotee of what she sometimes calls “It:”— the Fathomless Ground of Being that dare not be named or confined to a single religious tradition—or to religion at all, for that matter. For surely Asha as painter and artist expresses and relies on that same unnameable Source.

It was in that embracing spirit that in 1967, Asha and her first husband, Nooridinn, created the Lama Foundation in San Cristobal, New Mexico.

She was Barbara von Briesen Durkee then, and he, Steve Durkee—and with a little help from Ram Dass and various other counter-cultural heroes, they launched an enduring ecumenical spiritual retreat center that continues to thrive to this day, about 20 miles north of Taos.

While Asha is a senior teacher in the Sufi world, and travels extensively, deeply touching the lives of her students, unlike most people who take on that role, she is truly and simply “one of us,” and never for a moment has she pretended otherwise. In fact, so committed to this was she, that prior to forming Lama, she and Steve participated a traveling, multi-media performing troupe they called “USCO”—meaning, “the company of us.” And along these lines, one of her favorite quotes is “Our house shall be a house of prayer for all people,” and this was perhaps the unwritten motto behind the welcoming spirit of both the Lama Foundation as well as her home in Batesville, Virginia—a funky country house that has never had a lock or key, the front door perpetually open to all manner of friends, neighbors, wandering souls, people in crisis, even strangers. I’ve even observed Asha welcoming and engaging Jehovah’s Witnesses in a spirited conversation about “the Lord,” which for Asha could just as easily be Jesus as Allah, in order to meet whoever comes before her in a language they will understand.

The best place to meet Asha is on her porch. There, on the beat-up old couch, gazing out at her rugged land and flowers and the majestic mountains across the way, (the brush obscuring her “shoe garden,” a natural depository for abandoned footwear) she will make you a cup of tea and talk about anything and everything. Should the phone interrupt, she will answer it, but within a minute or so you will hear her say, “Hey listen, there’s a real live person here with me, and I feel that humans have priority over machines,” and thus excusing herself, return to you as if never has there been a guest more important than you.

And as she puts the phone down, you’ll notice it is smeared with red paint, or blue or green, as are her hands, and probably her face. For while known to many as their spiritual teacher, and by patients at University of Virginia Hospital as their nurse, Asha is a painter, and her life rhythm and style is primarily the wild, unkempt spirit of the artist. Although she is also a teacher and practitioner of the Japanese Tea Ceremony, with a great appreciation for the aesthetics of simplicity and order which surrounds that discipline, her wild artist-spirit tends to override that side of her, and so it’s quite possible that you might reach into her kitchen cabinet for a clean teacup and discover an old used teabag still clinging to the side. And if you glance over by the phone, you will see phone numbers scribbled directly on the white walls, along with perhaps a quote she found memorable, perhaps spoken by the five-year-old who lives down the block. Or perhaps it originated with Byron. And you’ll also see the pencil scratches on the wall marking everyone’s height, not only her grandkids, but the adults in the family as well.

I, like many who came before and after, showed up at her door in a state of emotional crisis. About two years after meeting her in Israel, a relationship had just ended abruptly and I was lost and despairing, and so I went to visit Asha and stayed for four years, gradually returning to myself in her nurturing presence.

Though she was not without human ups and downs and moments of upset, she was generally the happiest and most joyful person I had ever been around. Not only did my pain and depression fail to be a “downer,” she claimed that my company was a continuous delight, no matter how I was feeling. It almost seemed that the worse I felt, the more she insisted I was the life of the party.

In our four years as housemates, I cannot recall even a single moment of anger, disharmony or raised voices. The worst it ever got, perhaps, was minor irritation that say, a favorite book I might have lent her had somehow wound up in her giveaway pile and I ultimately found myself at the local used bookstore having to buy my own book back, at more than I originally paid!

But emotionally, it was the “cleanest” household I had ever lived in. And so I was initially perplexed when my parents visited me there, coming from their impeccably spotless, orderly suburban home in New Jersey, and all they seemed to see was a dirty shack of a house, filled with used, ratty furniture they were hesitant to sit on and hand-thrown ceramic tea cups they were hesitant to drink from. It was a revelation to me, for in my eyes, it was the cleanest house I’d ever been in, spiritually and emotionally, even amid the general funk to which I had grown oblivious.

I remember a conversation we had in her beautiful, Japanese-style tea hut, situated on her property down a wooded hillside along a stream, in which, as an example of something, she off-handedly inquired of me, “You know, the way you feel when you feel really, really deep down fine?” And then she continued speaking but I stopped listening because all I heard was a voice inside me responding, “No! I don’t know what it’s like to feel really, really deep down fine!” And the recognition of that difference in our interior experiences was somewhat shocking and revelatory to me. But it explains why so often those of us in crisis, or on the verge of spiritual collapse, stagger into her household broken, and stride back out days or months later put back together.

And it is not through anything she does—in fact, apart from the random cup of tea together on the porch, she is more apt to go about her business and ignore you! It’s one reason everyone feels so at home in her house—it’s clear that one’s presence is not imposing on her or inhibiting her activities or altering her day in any way whatever, unless she chooses to stop what she’s doing.

I remember when my first novel came out, after nearly twenty years of writing, revising, wishing, hoping, having multiple agents and multiple rejections—it was a significant milestone in my life, to say the least. I was cheered and praised by friends and family, acknowledging my achievement. Asha’s first response was to simply state, “You know, it doesn’t make me love you more,” instantly cutting through my whole, barely conscious drive for success, approval, acknowledgment, praise and yes, love, all of which were certainly tied into this event of my book coming out. She couldn’t offer me any of those things in response to my book coming out, because she already showered me with all of them just for being. There was nothing I could do to increase or diminish that gift. I knew her love and appreciation of me was already total and I could rest inside it.

When I would be endlessly struggling to figure out who to be and what to do with my life, she would comment, “You just need to find something to

do between breakfast and dinner,” or another time her solution to my life dilemma was to suggest, “Well you could mow my lawn.” Which I did.

In a similar vein, she once confessed that given how much she enjoyed her days and her independence, her ideal relationship would be someone with whom she could “spend midnight to six a.m.” But having survived two marriages that both ended unhappily, and having raised four extraordinary and beautiful daughters, she would often proudly announce to anyone listening, “I’m so happy my ovaries have dried up and I’m done with all that! It gives me more time and energy to paint. It’s all just a trick anyway, to keep the species reproducing.”

A striking beauty herself in her youth, I’ve seen her now, at 70, glance into the mirror, somewhat shocked by her own aging, largish body, and just declare the obvious: “Somehow the image I see looking back at me just doesn’t match my own aesthetic of beauty”—which is her way of simply acknowledging and summarizing—and letting go of—what would obsess and depress many women for years.

But all this brings us back to the art. Though she has had numerous shows over the years and her paintings hang in dozens of public and private spaces, she remains always in the freshness of “beginner’s mind” as a painter, always exploring new directions and techniques and expressions. The drawings in this book are the result of but one very particular moment of her art life. There are also huge, wall-size canvases of realistic oil paintings, luminous, nearly white abstract visions, a hundred varieties of small Buddhas, a “Feet & Pig” series, winged angels, Rothko-like monochromatics in blue, red, yellow and white, dragons for all the grandkids, on and on.

There is a retreat hut across the street from Asha’s house, about an hour’s walk up a mountain path. Shortly after her mother’s death in 1989, Asha created her own initiation vigil, shaving her head and going into solitary retreat for 40 days. These drawings document her inner journey. She did about one drawing and one watercolor a day.

Several years later, I decided to do a 40-day retreat up at the same cabin. By around day 23, I was on the verge of going mad and screaming, and I began telling myself, “You don’t have to stay up here just to prove something. You can quit.” Later that day I had to walk down to the appointed tree where every few days I left a note in a bucket, telling Asha if I needed more peanut butter or other supplies. In a moment of synchronicity and inspiration, I discovered that Asha had left not only more peanut butter for me that day, but the book you are holding in your hands, in its original, loose form. I took it back up to the cabin with me, and in reading the humorous, truthful, and poignant account of her inner experiences on retreat, I was completely restored. I saw myself on nearly every page, and my good humor returned. I remained up there the remaining days which turned out to be the most fruitful time of my retreat, and when my forty days were over, in the midst of one of the biggest blizzards in Virginia in quite awhile, I watched Asha tramping through the snow in the woods, coming up to escort me back into the world. May this delightful book likewise cheer your soul, restore your spirit, and escort you back to the world should you wish to go there.